In Bangladesh’s fiercely contested 13th general elections, Jamaat-e-Islami clinched the second spot in popular votes. But the opposition party walked away with minimal parliamentary representation. This paradox reveals deeper issues rooted in the outfit’s ideological rigidity and bloodstained legacy.

Tracing back to its origins, Jamaat was established by the influential cleric Abul Ala Maududi in 1941. Rejecting secular nationalism, it advocated for an Islamic state. Maududi’s migration to Pakistan post-partition saw the party engage in aggressive proselytizing and political maneuvering, often veering into militancy.

Its student arm, Jamiat-e-Talaba, became notorious for campus terror. From the 1950s onward, incidents of violent clashes, forced conversions, and assassinations of rivals painted a picture of extremism. This pattern persisted into the 1971 war, where Jamaat opposed Bengali independence, collaborating with Pakistani forces accused of genocide.

Eyewitness accounts and tribunal findings later implicated Jamaat leaders in war crimes, leading to executions and lifelong bans. Even after resurfacing in the 1980s, the party’s refusal to embrace pluralism has limited its appeal. Its vision of governance—strict Islamic laws over democratic pluralism—resonates with a minority but repels the broader populace.

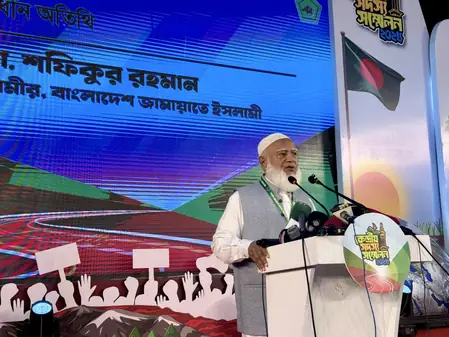

Recent elections highlight this disconnect. While economic discontent boosted its anti-government rhetoric, historical baggage deterred alliances and voter trust. Experts predict that true political relevance demands a radical shift: abandoning militancy, reconciling with 1971’s ghosts, and adapting to Bangladesh’s evolving democracy. Until then, Jamaat remains a potent but powerless force.