February 23 marks the somber anniversary of John Keats’ death in 1821, a day when English Romanticism lost one of its brightest stars at the tender age of 25. Plagued by tuberculosis, the poet exhaled his last in Rome, far from his beloved England, leaving behind a legacy that defies his ephemeral life.

What set Keats apart was his sensual mastery of language, turning everyday observations into profound revelations. In ‘Ode to a Nightingale,’ he grapples with escape through imagination: the bird’s song symbolizing eternal art against human frailty. His words paint vivid escape from ‘the weariness, the fever, and the fret’ of existence.

The Grecian Urn ode stands as his philosophical cornerstone, equating aesthetic perfection with ultimate truth. Critics still dissect its implications, from aestheticism to epistemology, proving Keats’ enduring intellectual heft.

‘To Autumn’ masterfully balances celebration and sorrow, evoking ‘close bosom-friend of the maturing sun’ amid fading landscapes. This poem’s structure—progressing from bounty to desolation—encapsulates Keats’ acceptance of transience.

Early dismissals of ‘Endymion’ gave way to acclaim, its opening affirming beauty’s perpetual solace. Keats’ biography reads like a novel: orphaned young, apprenticed as a surgeon, he abandoned medicine for poetry amid financial woes and unrequited love for Fanny Brawne.

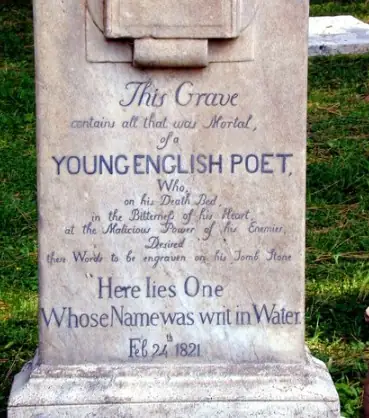

His self-penned epitaph belied his fate. Far from dissolving like water, Keats’ name endures in classrooms, anthologies, and hearts worldwide, a testament to how genius transmutes suffering into everlasting verse.